Local historian Tony Seward reflects on a four-day visit by artist, JMW Turner, right, who needed toughness and stamina to pack so much into such a short space of time…

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was born 250 years ago this month, possibly on April 23. Like his almost exact contemporary William Wordsworth (1770-1850), he was profoundly moved by the grand mountain scenery, lakes and waterfalls of the North. He made a number of tours seeking out the most picturesque scenes and antiquities in our region, but the focus here is on that undertaken in the summer of 1816, and within that, the four days he spent in Teesdale, from July 31 to August 3.

But first, a brief summary of the commission that lay behind this tour, and of his working methods. By this date, Turner was well established as one of the leading artists of the age. He was much sought after by wealthy patrons and publishers eager to commission work from him. One of the latter was Longmans, who engaged him to make 120 drawings of views in Yorkshire, for which he was to be paid 3,000 guineas, the most valuable commission he ever received. These were to illustrate A General History of the County of York, in seven folio volumes, by the Rev Thomas Dunham Whitaker, the best-known and most respected topographical writer of the time. The project was over-ambitious. In the end, only the first part, The History of Richmondshire, was actually published, containing just 20 of Turner’s drawings.

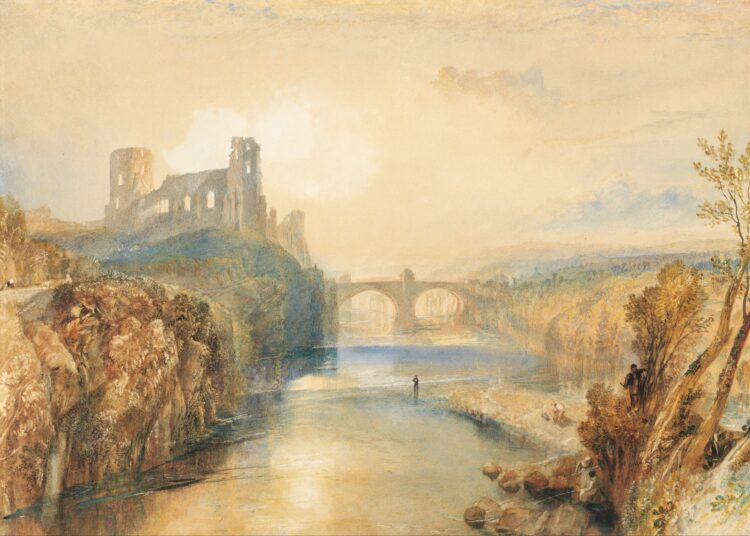

The term ‘drawings’ is somewhat misleading. There were in fact three distinct stages in their production, before they could be published. First, Turner had to visit all the viewpoints selected by the publishers and sketch them (on the way also recording any other subjects he thought might come in handy for future projects). In the winter, in his London studio, he would work up finished watercolours from the sketches. Finally, a skilled engraver would produce the copper plates based on these, ready for the printer. Some of the watercolours have been lost, so we only have the engravings based on them. These have the advantage of showing the details more clearly in reproduction, as here, and although they cannot render the light and atmosphere of the original, are often surprisingly successful in the attempt.

Turner arrived in Teesdale on July 31, staying initially at one of the inns at Greta Bridge and sketching around Rokeby – Mortham Tower, the Meeting of the Waters – before packing up for the day.

The following morning he visited Wycliffe before doubling back to walk up the Greta to the viewpoint from which he drew the old church at Brignall. This took him three hours and it was late afternoon by the time he reached his final destination of the day, Egglestone Abbey.

He probably stayed that night at Barnard Castle, before a long day of sketching and travel, taking in the castle and the view from Towler Hill, a detour to Bowes, then over the moors via Deepdale and Cotherstone to Middleton-in-Teesdale. Here, he enjoyed a dinner of ‘fillet of beef and potatoes, with potted trout’, and the landlord provided dry woollen socks and half pints of brandy, for visitors either to drink or rub into their heads for invigoration.

He needed such fortification for the rigours of the next day, Saturday, August 3. Unfortunately, 1816 happened to be the notorious ‘year without a summer’ when clouds of dust from a massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia led to long periods of darkness and rain, and failed harvests, in the northern hemisphere. Throughout his tour, Turner was working under great difficulties. The travelling was hard, and it was virtually impossible to sketch at the various viewpoints without his notebooks becoming soaked. It must have taken heroic determination to keep going, but even he was almost defeated by the journey out of Teesdale to High Cup Nick and Dufton. After sketching Wynch Bridge, High Force and Cauldron Snout, he set off over the high and lonely moors – as he wrote, ‘a most confounded fagg, tho on horseback…the passage out of Teesdale leaves everything behind for difficulty – bogged most completely Horse and its Rider, and nine hours making 11 miles.’

So concluded his four days in Teesdale. One can only marvel at the toughness and stamina which enabled him to pack so much into such a short space of time.