With the battle against Covid-19 still raginging worldwide, links are frequently made to Spanish flu in 1918. Historian Gillian Hunt takes a look at its impact in Teesdale

AS an ex-medical researcher and keen historian, I have a great interest in the 1918 influenza pandemic, known as Spanish flu.

It is thought that up to 100 million people may have died worldwide, more than were killed in the two world wars combined. It particularly affected young adults.

As we battle Covid-19, my thoughts have turned back to 1918.

Spain was neutral in the First World War and therefore more open about the influenza, so the name stuck.

Mass communication in 1918 was by newspaper and fighting countries limited their reporting for fear of affecting morale and damaging the war effort.

The Teesdale Mercury perhaps felt less constrained than national newspapers in what it said and its online archives are a valuable source of information about the disease in Teesdale.

Cause

THE paper first commented in July 1918 on the outbreak of influenza, expressing surprise at its appearance in the summer, when influenza was mainly a winter disease.

It put this down to a “lowering of vitality” . The doctors of the time had no idea that influenza is a viral illness – they mistakenly thought it was caused by bacteria and the Mercury noted the “direction of the wind and the density of the atmosphere affecting the spread of influenza in the hill country and the valleys” .

We now know that the 1918 pandemic was caused by the H1N1 strain of influenza and that the virus was very similar to bird flu. Bacterial infection caused the pneumonia which was a common complication, sadly often fatal. Spread of the virus, as with coronavirus, was by close person to person contact.

Prevention

DR William Hickey was the doctor in Gainford and immunisation officer for Staindrop district.

He would have been busy attending the sick in the district, although he certainly would not have been administering flu vaccinations as none existed.

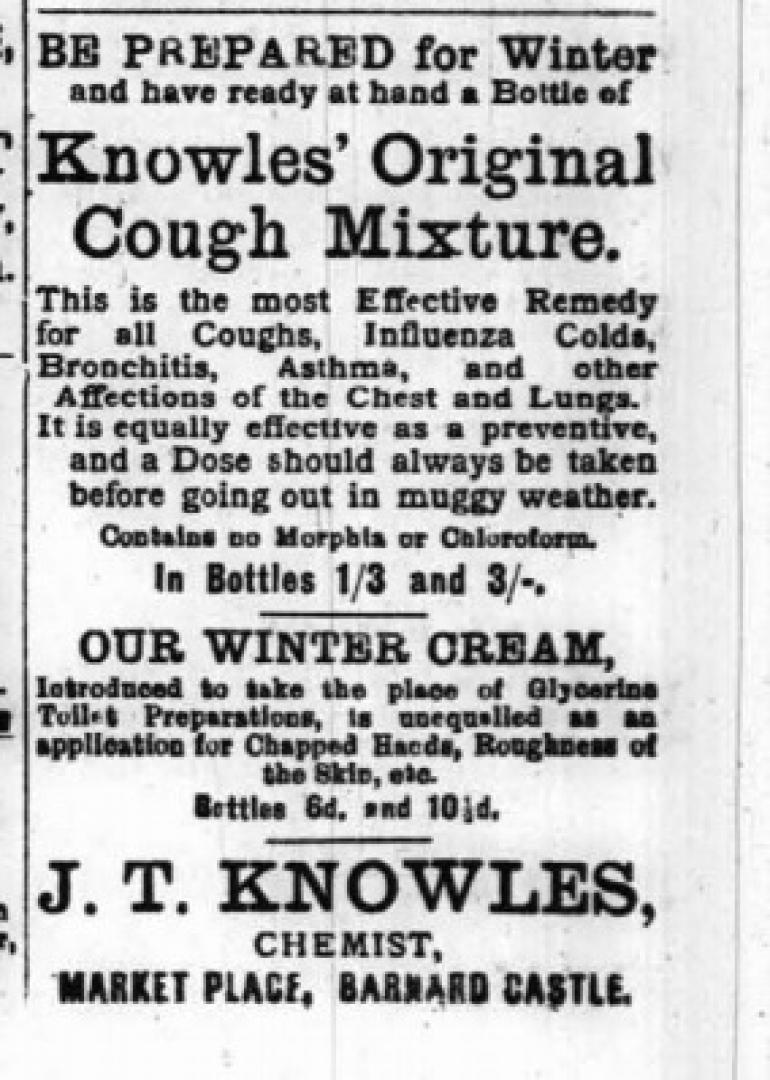

Knowles the Chemist, in Barnard Castle, was selling its own Original Cough Mixture which it advertised as effective against all respiratory complaints and as a preventative medicine if taken before going out in “muggy weather” .

Fortifying the body with beef tea was also recommended. Mr Simpson, the butcher at Cockfield, offered to deliver surplus beef to householders for the purpose.

Some of the preventative measures were more dangerous than the influenza. There was advice to smoke more, gargle with Milton fluid and use Jeyes’ Fluid disinfectant in the bath.

We are used to being told to wash our hands to prevent the spread of Covid-19. An advertisement for Lifebuoy soap in 1918 claimed that washing with the soap before attending school would protect pupils against infection. At first, there was reluctance to close schools.

By November 13, 1918, influenza was prevalent in Gainford. Six children had been sent home ill from the village school and attendance was only half what it should have been.

No Social Distancing

THE advice given by doctors in the area in the summer of 1918 that anyone showing symptoms of influenza should immediately go to bed in isolation was correct.

However, advertisements and reports in the Mercury suggest that there was little social distancing among the healthy and life went on more or less as normal, with council meetings, church services, films at the Victoria Hall cinema, in Barnard Castle, concerts to celebrate the armistice and advertisements encouraging shopping for Christmas goods.

How many victims?

THE Spanish flu eventually disappeared in the summer of 1919 but how many victims were there in Teesdale?

It was at its peak in the autumn of 1918, reflected in the total of 153 deaths recorded in the Teesdale district (which included Gainford, Winston, Ingleton and surrounding villages) between October and December 1918.

The Mercury commented in December 1918 on the “alarming death toll” flu and pneumonia in the district.

Behind the statistics are human tragedies and so far I have identified 11 of the 153 deaths as being due to influenza, all under the age of 30, with three of these at Gainford.

In some communities, it is possible that there were more victims of Spanish flu than there are names on the First World War memorial but their deaths are largely forgotten and they have no monument. We should remember them.

I am researching a paper on Spanish flu in Teesdale for The Bowes Museum to archive alongside their First World War material.

If anyone can tell me more about Spanish flu in Teesdale, or identify any victims (no names will be used without permission), please contact me on bbeagle

@btinternet.com