ON February 6, 1918, the Mercury reported that George Bell, a Staindrop farmer, had appeared at the Police Court in Barnard Castle, charged by the Rural Food Committee Inspector with selling butter “at a figure beyond the maximum price laid down by the Food Controller” .

The war had placed the supply of food under tremendous pressure.

In 1914 Britain produced only 40 per cent of its needs and the German U-boat campaign severely restricted imports. Home production fell because men and horses were taken by the army.

Women, boys, older men and prisoners of war were put to work on the land and greater mechanisation was introduced. Everyone was encouraged to grow food and allotment associations were founded in Barnard Castle, Startforth, Cotherstone and other villages.

Shortages resulted in rising prices, hence the need for government control all aspects of the food chain, including price controls. George Bell had sold 10½ lbs of butter to Staindrop grocer Mr Jackson, at 2s 4d per lb who then sold it on at his usual profit of 2d per lb. This was 1d more than the legal wholesale and retail prices.

George Bell pleaded that there was no intention to defraud, there was confusion over different prices in each district and that he had recently spent £140 buying three cows to increase production (implying greater contribution to the war effort). Nevertheless, he was found guilty and fined £1.

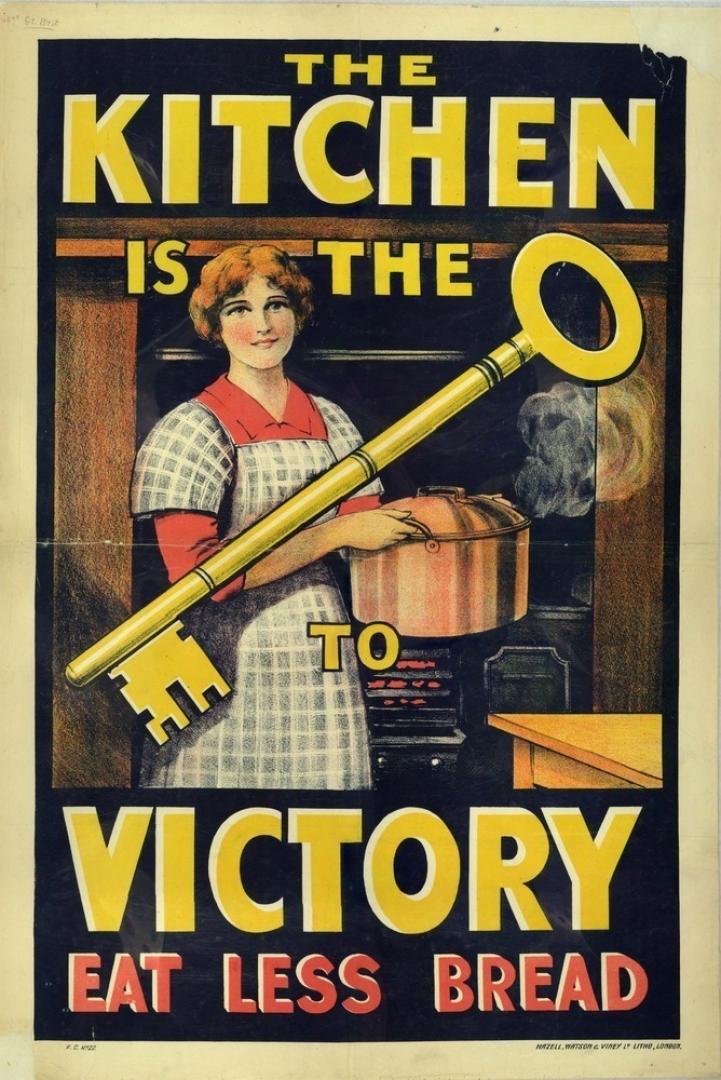

It was essential to reduce the consumption of precious resources needed for the war effort. A National War Savings Committee was set up with local branches to encourage the economical use of fuel and food. Slogans such as “save or starve” were used, people were encouraged to have meatless days, give up sugar and recipes were devised that used less flour.

Patriotic duty required restraint from all classes. The Times reported in February 1917 that Eton schoolboys were to be limited to the advised rations of bread, meat and sugar.

By the end of 1917 discontent was rising. In London there were long queues at provision shops in the poorer districts, although there is no evidence from The Mercury that such shortages were prevalent in rural areas.

In January 1918 there were demonstrations and disorderliness in many cities.

It was obvious that voluntary restraint was not enough.

Some towns had already introduced rationing schemes and it was inevitable that fairness required a nation-wide rationing programme.

The Mercury on February 13 reported how first to be rationed was sugar and by the end of April meat, butter, cheese and margarine were added to the list (2lb of meat, ½lb sugar and ½lb total fats per person per week).

Ration books were issued and families had to register with local shops.

Supplementary cards went to heavy workers such as miners and farm labourers, also adolescents and women who could make a case for extra needs.

Mrs Bell-Irving sent rabbits to Barnard Castle which were distributed to worthy recipients by the clergy. The Rural Food Committee inspector reported that a soldier’s wife in Cockfield was unable to get enough milk for her 12 children and a priority scheme was adopted to supply milk to invalids and children under five, “subject to the consent of the Food Controller” .

As a result of these measures, although there was a degree of scarcity, Britain was never faced with food shortages on the same scale as Germany, where in the winter of 1917 to 1918, more than 500,000 German civilians died of starvation.

June Parkin