Memories of Barnard Castle’s gasworks are now fading but the site, which was in use between 1834 and 1952, was once the town’s powerhouse. Historian Tony Seward takes a look back at its industrial history

THE Roman Way picnic site by the river has recently been tidied up by a group of dedicated volunteers led by Roger Peat, as featured in the Teesdale Mercury last month.

Well known to local walkers and visitors, it features stone benches with sculptures of a sheep and a water nymph, and a pavement depicting river creatures, designed by sculptor Keith Alexander and children from Bowes Hutchinson’s School. The current name recalls the Roman road which crosses at this point.

As the years pass fewer will remember that, for well over a century, this parcel of land on the riverbank was literally a power house for Barnard Castle and the surrounding villages.

A joint stock company to supply coal gas was established in 1834, and the works opened the following year. Originally the gas was produced solely for lighting. The streets were illuminated by 82 lamps at a charge of £90 per annum, 18 being kept alight every night from dusk to dawn, the other 64 until 11pm every evening except Saturday – when they were allowed to burn until midnight. Two lamplighters are listed among the employees of the company in 1891, both aged 21.

Town gas

UNTIL the arrival of abundant supplies of natural gas in 1967, most towns and villages of any size in Britain had their own gasworks, providing gas to the community for heat, light and cooking. Gainford, Staindrop and Middleton-in-Teesdale all had gas plants, as did the private estates of Raby Castle and Rokeby Hall.

The process was discovered in the 1790s and the first company selling gas to the public was founded in 1812. It operated by heating coal to a high temperature in coke ovens. The off gases liberated by this carbonisation were then collected, scrubbed and distributed to the surrounding area by a network of pipes. Coal gas consists mainly of combustible gases including hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, and ethylene – quite a dangerous cocktail.

The scale of the operation in those early days is indicated by the fact that 3,052 tons of coal were consumed in the ten years to 1849. In 1845, just over 222 tons produced 372,200 cubic feet of gas, but this ratio greatly improved as the plant became more efficient over the years. It should not be forgotten that the costs were considerably offset by the sale of coke and other by-products resulting from the process.

The gasworks

THE key stages of the process were as follows:

Coal was delivered to the retort house, and fed into coke ovens by the stokers; the gas thus produced passed through a washer and de-tarrer for removal of tar and ammonia; then through four boxes of iron oxide for removal of hydrogen sulphide, and finally to the holders for storage.

The only building still remaining, to the north of the picnic area, is the governor house. This contained two Donkin “governors”, installed to regulate gas pressure in response to frequent complaints from customers about pressure fluctuations. Built in 1902-3, it was retained when the rest of the works was demolished in 1992, as supply pipes still ran through it.

There were also store houses, an engine house, a weigh cabin, a manager’s house, and an ammonium sulphate plant for converting the ammonia by-product into fertiliser for local farmers.

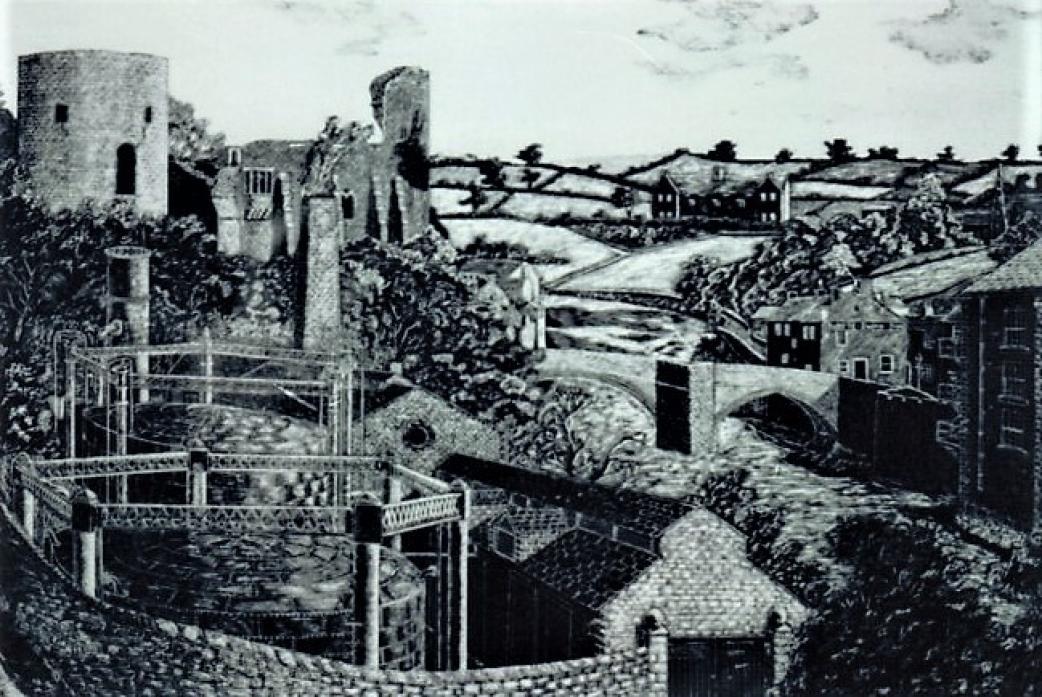

The gasholders

THE old town gas plants are mainly remembered nowadays, if at all, by the often impressive holders preserved as a feature in some towns and cities.

To the casual passer-by, they would have been the most arresting aspect of the works, often recorded in photographs and paintings of the period.

There were four holders on our site, built at different dates, but only two were in use at any one time. The first, east of the retort house, was demolished in 1899 and converted into a tar well. The fourth, built around 1924, had a capacity of 150,000 cubic feet and by 1965 was the last one remaining.

Final days

WHILE we tend to romanticise what remains of old industrial sites, at the time many regarded them simply as eyesores, especially when they became derelict at the end of their working lives.

In our area, famed for its natural beauty, local photographers Elijah Yeoman and Harry Ward did their best to exclude the gasworks from views of the castle, using a massive holly tree to block it out.

Gas production ceased in 1952, and over the next 40 years the area became a post-industrial wasteland.

So councillors and local residents warmly welcomed the news (TM, April 22, 1992) that the last rusty old gasholder was to be taken down. But there was one final hurdle to overcome before the site could be converted into “a pleasant picnic area”.

The land had to be thoroughly decontaminated, and the polluted “soil with noxious vapours” removed by the gas company – a fairly major operation.

Accordingly, Cllr John Watson asked for an assurance that the road to the site would be restored completely after the work, as damage would be caused by wagons taking away the material.

Apart from the governor house, is there any remaining trace of all this activity taking place over so many years?

Well, perhaps – as you walk by you may just catch a whiff of coal tar in the air, a lingering ghost of the millions of cubic feet of gas produced here in former times.

Based on two unpublished booklets, ‘Barnard Castle Gas Company’ (2009), and ‘Gasworks in South West Durham and North West Yorkshire’ (no date), by Charles Lilley, archived at The Fitzhugh Library, Middleton-in-Teesdale. For information about the library’s resources and opening hours, go to www.thefitzhughlibrary.co.uk With grateful thanks to Mr Lilley, and to Cath Maddison and Derek Sims at the library for their help in preparing this article.