This year is thought to be the 700th anniversary of the birth of John Wyclif. Wycliffe Church warden Keith Miller delves into his past…

In the heart of the Houses of Parliament, in Westminster, stands St Stephen’s Hall. In the 1920s, it was decided that eight murals should be painted to decorate its walls, representing key moments in the history of Britain.

Perhaps not surprisingly these include such momentous events as King Richard I setting forth on the Crusades, King John conceding to the barons at Runnymede, Queen Elizabeth I commissioning Sir Walter Raleigh to search for the New World of America, and the Union of England and Scotland in 1707.

What might cause surprise, however, is the subject matter of one of the remaining ones. It is entitled ‘The English People reading Wycliffe’s Bible,’ and represents the long struggle for religious freedom.

In a society which, to a large extent, no longer ‘does God’, it might seem an extraordinary and somewhat bewildering choice. However, in recent times, the left-wing parliamentarian, Tony Benn, kept a copy of the painting as a reminder of how people at all times have placed their lives at risk by defying the authorities to read banned documents.

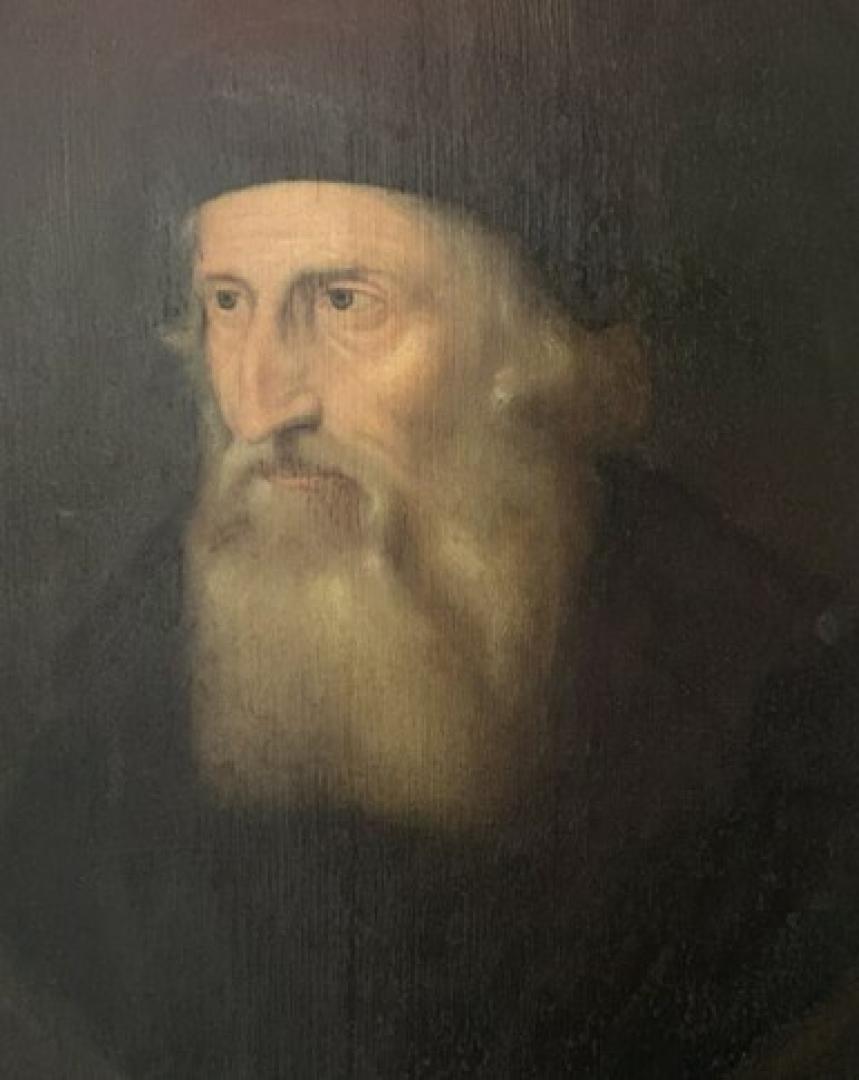

But who was John Wycliffe, or Wyclif, as his name is more commonly spelt? When and where did he live, and why is he important?

Records surviving from medieval England are frequently incomplete, and the problem is compounded in his case as the Wyclif family regarded him as a heretic, destroying references to him in family documents.

However, it is clear that his family took their name from the hamlet of the same name, near Barnard Castle, where they were lords of the manor, and his parents, Roger and Katherine, are buried near the altar in Wycliffe church.

As to the date of his birth, historians are unable to agree, although a memorial plaque at Lutterworth, Leicestershire, where he was vicar when he died in 1384, suggests that he was born in 1324.

If this is correct, then this year would mark his 700th anniversary. There is also some confusion as to where exactly he was born, caused by the 16th century antiquary, John Leland.

Leland wrote that “some people say” that he was born at Spresswell, which has been interpreted as being Hipswell, near Richmond. However, the family name and the fact that his parents are buried in Wycliffe church suggest that this is incorrect.

It is documented that in his teens, John travelled to study at Oxford University, where he established a reputation for his intellect and intelligence, becoming Oxford’s foremost philosopher and theologian.

He became master of Balliol College (founded by John de Balliol of Barnard Castle). It was a time of great upheaval, with the Black Death claiming as much as a third of the population in 1348-9.

The Church exercised enormous power, as well as wealth. The language of education and the Church was Latin. The language of the Court was French. Meanwhile, the rest of the population spoke a form of middle English. Very few could read. Wyclif attacked the corruption that had led to the sale of pardons, the lack of concern for the poor, and the failure to follow the teaching of the Bible.

At first, he had powerful backers, including John of Gaunt, son of Edward III. The English Church was required to send large sums of money to the Pope, who was helping to fund the French armies who were fighting English soldiers in France!

In 1374, Wyclif was part of an unsuccessful commission sent to Bruges by the government to attempt to resolve matters.

He was condemned by Pope Gregory XI and faced trial before the Bishop of London, only avoiding conviction and probable death by having the support of Gaunt and others.

Other attempts to have him convicted similarly failed.

The Royal Court supported Wyclif so far as he opposed the power of the Church, and the demand that money be sent to the Pope. However, as his attacks became more doctrinal, relating to specific beliefs which had nothing to do with secular power, nervousness increased. In 1381, the Peasants’ Revolt took place which, although not instigated or supported by him, involved attacks both on monastic and secular properties.

It is not known whether Wyclif returned to Teesdale, although there is evidence that, together with his mother, he was involved in the appointment of a new rector for Wycliffe church in 1369.

Wyclif died at Lutterworth in 1384. Although his work in translating the Bible into English had only just begun, his supporters continued the task. His teachings did not die either.

These included not only the right for people to be allowed to learn the scriptures in their native tongue, but also that the Bible should be the sole source of the doctrine taught by the Church. It followed that corruption should be resisted, even more so when it came from the most powerful institution then in existence.

Through his followers, disparagingly known as “Lollards” , his views gained support in Bohemia where the Czech reformer, Jan Hus, was to face execution in 1415. In Italy, the heart of the Church, the preacher and theologian with similar views, Savaranola, suffered the same fate in 1498.

Far from dying out, the views which Wyclif had expressed gained strength. Martin Luther, the name best known in connection with Protestantism, paid tribute to him. Not surprisingly, Wyclif is generally recognised as being the “Morning Star of the Reformation” .

l This summer, there will be a programme of concerts, talks, and the showing of a film about the life of John Wyclif, all to be held in St Mary’s Church, Wycliffe. For full details, please contact the churchwarden, Keith Miller, at [email protected] or call him on 01833 627540.