In an occasional column, Dorothy Blundell takes a look at the opening of The Bowes Museum where she is a volunteer

standfirst goes something likeAFTER 30 years in the planning and building, today was the day when doors would open. And what a party it was going to be: the whole of Barnard Castle on holiday, all the main streets decked out in colour – flags fluttering and roadside flower arrangements looking lovely.

Never before had there been a better reason for the whole town to celebrate than now – June 10, 1892… the first day of The Bowes Museum.

It was “tolerably good” weather and, from an early hour, the streets were thronged with visitors, some of whom arrived on special excursion trains. The Teesdale Mercury account was extensive, devoting thousands of words to describing the colourful scene, listing who was present, reporting the speeches and the toasts verbatim.

“There is probably no finer building in the provinces than The Bowes Museum,” said the report, “if indeed there is a finer one in the metropolis, and the good people of the neighbourhood were justly impressed by the importance of the occasion.

“Not since the town of Barnard Castle was founded in the 12th century by Bernard Baliol… has such an important and interesting event taken place within our borders.

“There were banners floating from the windows, rows of tiny pennons stretched across the roads, festoons of paper roses in prominent places and scrolls bearing inscriptions of welcome and congratulation. Outside walls of houses were decorated in green boughs and fresh flowers and were exceedingly pretty.

The railway station entrance was charmingly set off by banks of ferns and other plants, and along Galgate, Market Place, the Bank and Newgate, were Venetian (decorated) masts.”

That this was a big deal for Barnard Castle was no doubt. But the “why?” was not addressed. Why build a 17th century-style French palace in the middle of Teesdale? What were the founders, John and Josephine Bowes thinking?

Neither was around to ask. Josephine had died 18 years earlier, just days after the last roof timber had been placed, and John had died almost seven years earlier.

At least he had lived long enough to appoint the first two curators and see how they began the enormous task of unpacking the hundreds of boxes of carefully wrapped objects and paintings.

So was the couple’s motivation to leave a legacy, to elevate the souls of the working classes or because of a sense of philanthropy expected from John’s wealthy status?

Maybe it was a bit of all three. There are documents in the museum archive which offer a little insight into their inspiration: they had noted wall colour and picture framing techniques of the Louvre, roof lights and archway-linked picture galleries of Munich’s Alte Pinakothek (art museum) and architectural elements from the destroyed Tuileries Palace.

In 1917, the Newcastle Chronicle, said: “The building is to the solid market town of Barnard Castle what a wedding cake is to a buffet of Scotch eggs and crisps.” Architectural historian Nicholas Pevsner said it was “big, bold and incongruous, looking exactly like the town hall of a major provincial town in France” . In fact, according to curator Owen Scott, the initial idea had been to site the museum in France.

In Handbook to The Bowes Museum, published in 1893, book he writes: “They abandoned this from a consideration of the permanently unsettled state of politics in France.

They thought there was less chance of revolutions occurring, in which the works of art might be injured, in England.

They ultimately decided upon Barnard Castle, as being a town with which Mr Bowes’ ancestors had been connected for many centuries, and the nearest place of importance to Streatlam Castle.”

Back to 1892 and that historic day, at 11.30am there was a procession through the town, made up of representatives from all the town’s public bodies and other groups, plus hundreds of school children, all led by the band of the 3rd Battalion Durham Light Infantry.

The band played The Battle of Magenta, Her Bright Smile Haunts Me Still and Old Memories. The route was thickly lined with sightseers and, at the museum gates, the procession passed between the ranks of a guard of honour composed of the 2nd Battalion DLI.

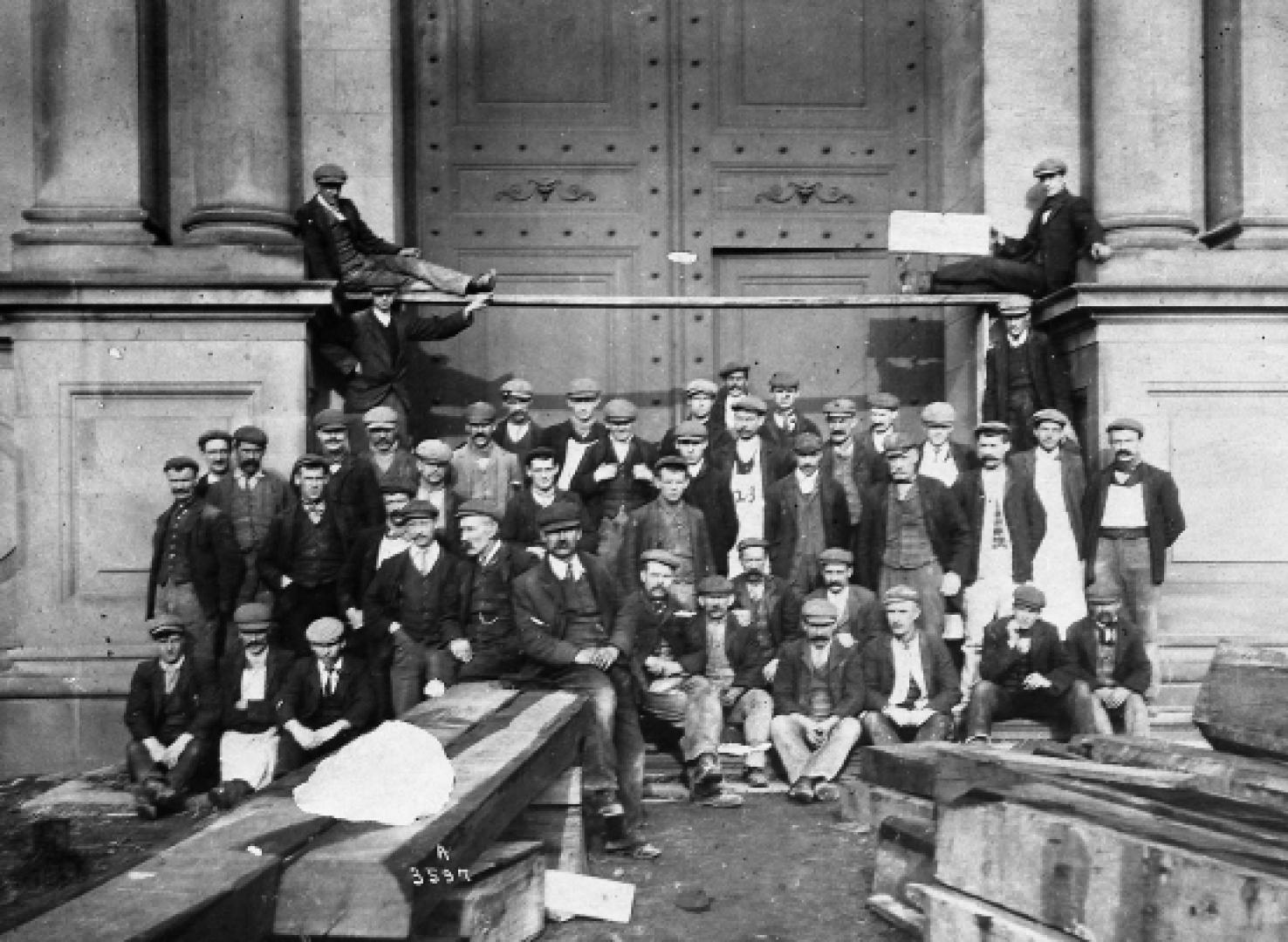

The terrace and park were teeming with an estimated 4,000 people. Speakers and other VIPs were grouped on the building’s entrance steps. Of the handful of people who had been present at the private ceremony, in November 1869, to lay the foundation stone, only one survivor – the builder, Joseph Kyle, was there.

Sir Joseph Pease, MP, son of Bowes’ friend and former Parliamentary colleague, declared the building open.

He read from Josephine’s will, and commended her words: “I request and adjure the inhabitants of Barnard Castle with common accord to aid the committee as far as possible in guarding this museum, the contents of which it has taken so much of my time and trouble to collect and bring together in this park.”

Sir Joseph added his own thoughts: “I consider that today we have opened to the public a priceless boon… leading people’s minds from those things that are gross and grovelling and dying, to those things which are high in art, which raise up the human mind…”

Then, amid tumultuous cheering and waving of hats, the 17ft tall, solid iron front doors were thrown wide and for the rest of the day thousands of curious visitors filed inside, eager to see for themselves the treasures within. Elsewhere in the town, at the King’s Head Hotel, there was a public lunch presided over by the 13th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, a cousin of John Bowes.

The Mercury reported: “Sir Joseph proposed they drink in solemn silence to the memory of the late Mr and Mrs Bowes. Mr John Grieveson, of Galgate, most admirably proposed the toast to the committee of trustees and was quite confident that things would now go without a hitch.”

Mr Scott, in his museum handbook, echoed the sentiment: “The museum has not yet surmounted all its difficulties, but it has so far done as to justify good hope for the future.”

Six years after the giddy excitement of that opening day, the museum closed because of lack of funds – a situation not helped by the discovery of wet and dry rot which meant that all the oak beams had to be replaced with steel girders.

The museum eventually reopened in 1909, but more financial problems were to follow as the years progressed.

And so to 2022. There has been many a hitch along the way, but the museum has endured.

And while there might not be any evidence of tumultuous cheering and waving of hats to mark its 130th anniversary, and even though there will always be more difficulties to overcome, we should all be filled with good hope for the museum’s future and the next 130 years.