SOME 450 years ago, Barnard Castle was drawn into the rebellion known as The Rising of the North.

Many of the population in the region had never become reconciled to England’s break with Rome and in 1569 the Earls of Northumberland and Westmoreland led a revolt to re-establish the old religion.

Their aims, though confused, included a desire to settle the succession on the Roman Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, who was then in captivity in England, and her offspring.

Charles Neville, Earl of Westmoreland, owned both Brancepeth and Raby Castles, while Thomas Percy, Earl of Northumberland, was based at Alnwick. They mustered their followers at Brancepeth and marched south as far as Bramham Moor, near Wetherby. They then turned back and, passing through Ripon and Richmond, laid siege to Barnard Castle.

In the course of their march through the North, groups of rebels forced people to attend Roman Catholic services at Darlington and Durham, broke communion tables and burned service books at the cathedral – a particular grievance had been the imposition of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer).

Their faith was symbolised by the banner they carried depicting the Five Wounds of Christ, also used on the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536-7, an earlier attempt to reverse Henry VIII’s suppression of the old religion.

Sir George Bowes (1527-1580) was an ancestor of John Bowes, the founder, with his wife Josephine, of The Bowes Museum. A devout Protestant and loyal servant of Queen Elizabeth, he had been watching developments for some months from his seat at Streatlam Castle. An experienced military commander, he realised that the royal forces were not yet in a position to confront the rebels head-on in open battle. He had therefore set in hand detailed preparations for holding the castle at “Barney Castell” until reinforcements could be brought up from the south.

The garrison consisted of more than 100 local men, with 200 foot soldiers and 100 horsemen drawn from the gentry. They were well armed, with 104 spears, 85 bows, and seven portable guns (arquebuses) which could be mounted on tripods. Facing them were up to 1,500 horsemen and 3,000 foot soldiers.

The siege began on December 1, 1569, and lasted for 11 days. The rebels began by attacking the walls on the town side and after three days broke into the town ward, the defenders falling back across an inner moat and continuing the fight from the middle ward. Sir George and his family were living in the inner ward.

As conditions became harder, with food and water running low, men began to desert. Finally, one night, 226 leapt over the wall and joined the enemy. Of these, as Sir George reported to Secretary of State William Cecil, “thirty-fyve broke their necks, legges and arms in the leaping.” Shortly afterwards, 150 men who had continued to guard the gates flung them open and also joined the rebels.

After this, there was no alternative but to surrender.

Sir George and the remaining defenders marched out and capitulated to the Earl of Westmoreland, who allowed them to march away unharmed.

Tying up the rebel forces at Barnard Castle had allowed the Queen’s armies time to gather in strength, and the rebellion was crushed soon afterwards. The Earl of Northumberland was executed, still asserting the Pope’s supremacy, and the Earl of Westmoreland fled into exile, never to return.

Sir George was tasked with organising the savage reprisals which followed the rising – the Queen ordered that 700 of those involved across the North should be executed. Each town and village was assigned a quota of men to meet the target.

Sir George may have been the less inclined to show mercy when he discovered, on returning to Streatlam, that his castle had been trashed and looted by the rebels.

Nevertheless, he was chided by the authorities for being too dilatory in carrying out the executions. Some villages escaped altogether but Staindrop, for example, was unlucky, losing seven men, while only 16 of 83 known rebels were executed in Darlington. The rising is seen as a major turning point in the history of the North. It was the last attempt to re-establish the old religion and way of life, and henceforth the region was to become fully integrated into the Protestant Reformation initiated by Henry VIII.

By the late 18th century the rising was being romanticised in poetry and legend – a ballad on the subject was included in Bishop Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). Wordsworth reworked this in his White Doe of Rylstone (1815), several verses of which are devoted to the siege.

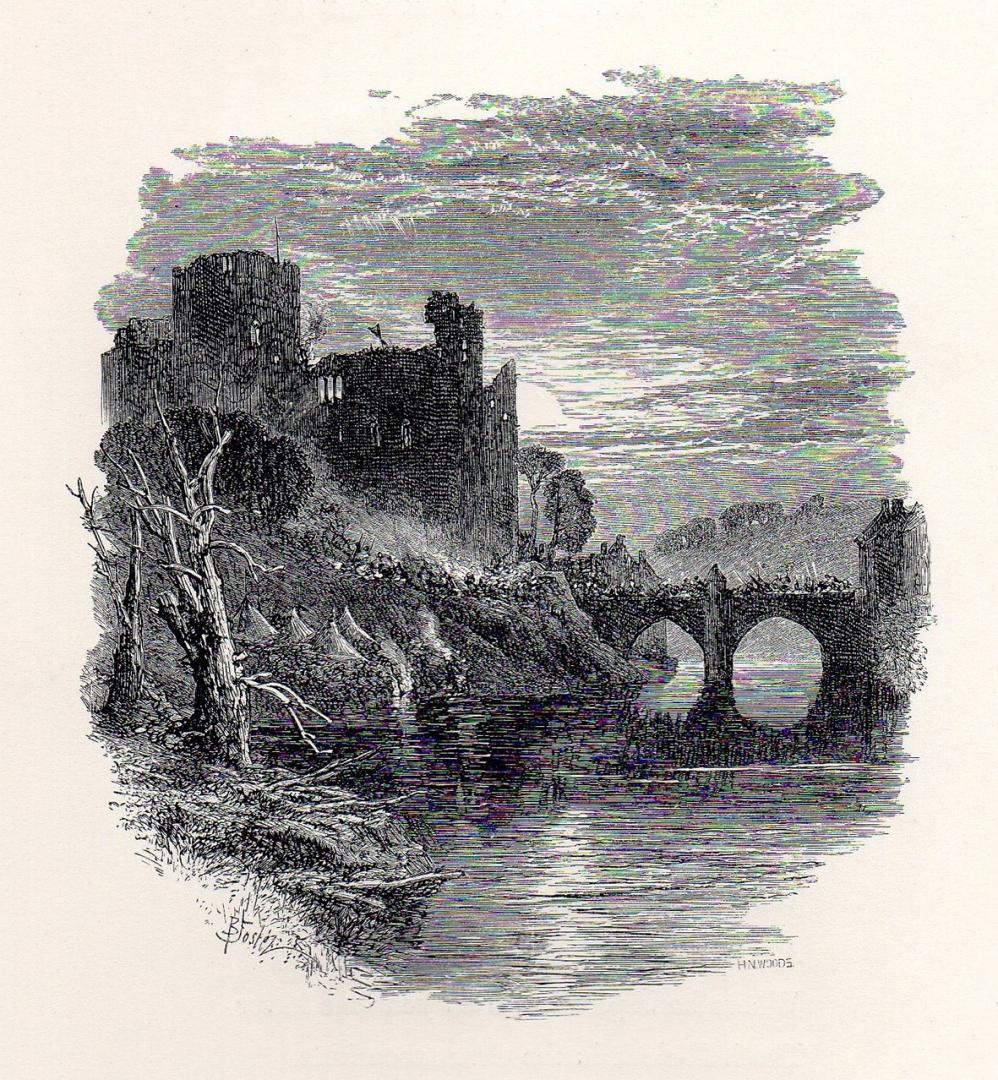

Pictured above are pages from a sumptuous Victorian edition, with illustrations by Birket Foster.

It must be noted that the artist has shown the castle as the romantic ruin it had become by the 1800s, making no attempt to imagine it as it would have been in 1569.

An important primary source for historians of the rising is a collection of documents discovered in a cupboard at Gibside in 1833.

The Hartlepool antiquarian Sir Cuthbert Sharp undertook the task of preserving and transcribing these, and published them in 1840 as Memorials of the Rebellion of the Earls of Northumberland and Westmorland. The manuscripts were bound up in 18 volumes, one of which is held by The Bowes Museum – crucially for our purpose, this volume contains Sir George Bowes’s correspondence during the rebellion, consisting mainly of detailed reports to the authorities as the crisis develops, and the measures he is taking to deal with it.

Extracts from the letters will form part of a small display in the museum foyer through December 2019 and January 2020, to mark the 450th anniversary of the siege.