In an occasional column, Dorothy Blundell takes a sideways personal look at what goes on behind the scenes at The Bowes Museum where she is a volunteer

YOU will have heard the saying: “like a bull in a china shop.” Well, this is a story about an almost forgotten rhinoceros in The Bowes Museum.

Every now and then an object, or sometimes a group of objects, leaves the museum to go “on tour” .

Museums, paradoxically, are fiercely possessive of their collections, proudly boasting about what makes them special, while at the same time they are also supportive of one another with expertise, information and temporary loans of items by special request. Past examples include the Silver Swan (London’s Science Museum in 2017), the dog portrait ‘Bernardine’ (Kennel Club’s Labradors in Art in 2016) and some of The Bowes’ world-renowned Spanish paintings, which were loaned out to the Wallace Collection in London two years ago, and are due to travel in September this year to Dallas, Texas, for five months. This collaborative loan-share arrangement widens the numbers of people who can appreciate a fraction of the treasures which John and Josephine Bowes collected and, importantly, it spreads the word about their magnificent museum in Barnard Castle. As a bonus, the loan of the item sometimes adds to the museum’s sum of knowledge. Take Clara for example.

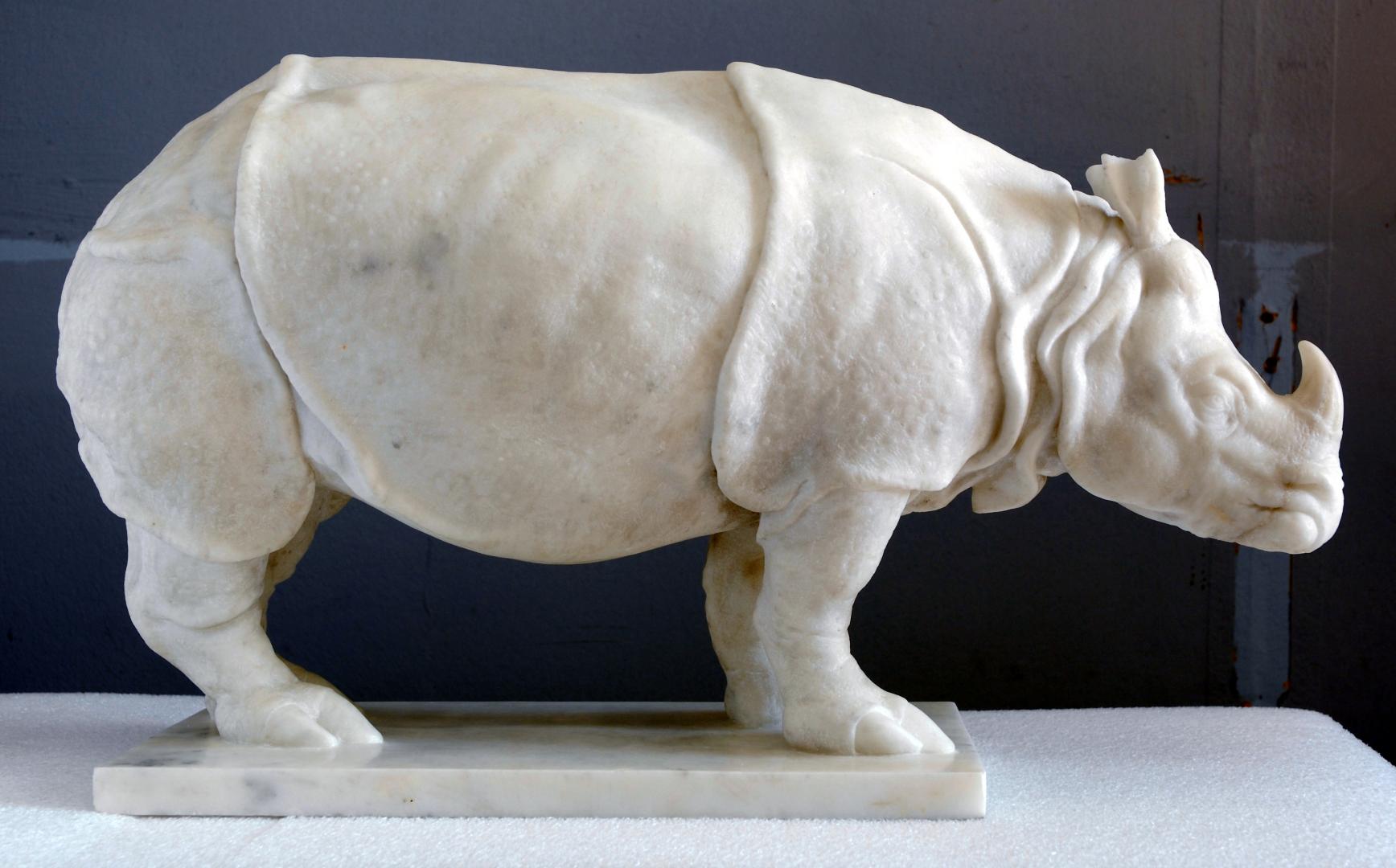

A small, white marble statue of a rhinoceros (roughly 2ft high) was among thousands of objects acquired by John and Josephine during their 15-year shopping spree which lasted until 1874. The rhino has stood in the galleries ever since the museum opened in 1892. The statue was unremarkable and the reason for its purchase unrecorded. That was until about 15 years ago when a German museum asked to borrow it. “Yes,” said The Bowes Museum, “but why?” And so Clara, or at least her story, lives again.

Clara was no ordinary rhino. Born in India around 1738 and orphaned while still a calf, she was a house pet adopted by a Dutch trader Captain Douwe Mout van der Meer who for 17 years took her travelling around Europe.

She wowed the crowds – from royalty to peasants. She was, simply put, an animal superstar. Remember, this was a time when little was known of the wider world and her astonishing appearance captured the imaginations and the hearts of the many thousands who queued to pay to see her. She created a sensation wherever she went, only the fifth living rhino to reach Europe.

Artists, poets and musicians were inspired and rhinos became popular depictions in European fine and decorative art, including pottery, tapestry and even French 18th century clocks.

Her portrait can be seen in a drawing by Anton Clemens Lünenschloss in 1748 (he called her Jungfer Clara or Maid Clara) and Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686 -1755) whose 10ft by 14ft 9in painting in 1749 was virtually lifesize. The Bowes Museum’s version of Clara was copied from the original made for the Jardin des Plants (botanical gardens) in Paris.

Look out for her when you are next in the museum and think how lucky it was that only one Clara statue was bought. More than one… and displaying them in the china galleries would have been tempting providence: a group of rhinos is called a crash.

Visit thebowes

museum.org.uk